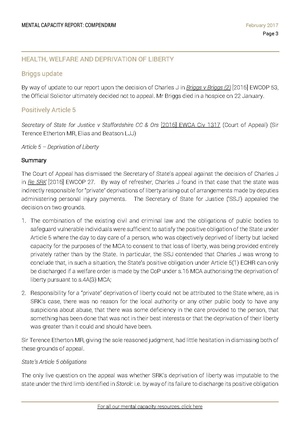

SSJ v Staffordshire County Council and SRK [2016] EWCA Civ 1317

(Redirected from SSJ v Staffordshire County Council and SRK (2016) EWCA Civ 1317, (2016) MHLO 55)

Essex

This case has been summarised on page 3 of 39 Essex Chambers, 'Mental Capacity Report' (issue 73, February 2017).

ICLR

The ICLR have kindly agreed for their WLR (D) case report to be reproduced below. For full details, see their index card for this case.

Court of Appeal

Staffordshire County Council v K

Sir Terence Etherton MR, Elias , Beatson LJJ

Mental disorder — Incapable person — Deprivation of liberty — Severely injured adult lacking mental capacity to make decisions as to care and residence — Deputy appointed to manage property and affairs — Damages award used by private sector providers to provide residential property, care and support — Care regime amounting to objective deprivation of liberty — Whether deprivation of liberty to be imputed to state — Whether welfare order required to ensure lawfulness of care regime — Human Rights Act 1998 (c 42), Sch 1, Pt I, art 5 — Mental Capacity Act 2005 (c 9) (as amended by Mental Health Act 2007 (c 12), s 50, Sch 9, para 10), ss 16, 64(5)(6)

K, an incapacitated adult who had been severely injured in a road traffic accident, was awarded substantial damages in court proceedings which were used by his property and affairs deputy, a private trust corporation, to provide a specially adapted residence and to fund the regime of care and support provided by private sector providers. The local authority, having been informed of the arrangements for K’s care and the arrangements having been registered with the Care Quality Commission, applied to the Court of Protection for a welfare order under section 16 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The parties accepted that the arrangements satisfied the first two components of a deprivation of liberty within article 5 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, namely (i) the objective component of confinement in a particular restricted place for a not negligible length of time and (ii) the subjective component of lack of valid consent. However, the Secretary of State contended that the third component, namely the attribution of responsibility to the state, did not apply to the privately funded and arranged care regime, or to others in an equivalent position, and therefore there had been no “deprivation of [K’s] liberty” for the purposes of the 2005 Act and consequently the care regime could lawfully be put in place without a welfare order being made under the Act. The judge granted the application for a welfare order, holding that a “deprivation of a person’s liberty”, as defined in section 64(5) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, as amended, occurred only where all three components of a deprivation of liberty within article 5 of the Convention existed, including the third component of the attribution of responsibility to the state. He further held that none of the public bodies or individuals involved, neither the court which had awarded K damages, nor the Court of Protection when appointing the deputy, nor the deputy, nor the local authority, nor the Care Quality Commission, amounted to direct involvement on the part of the state so as to attribute responsibility to it, but that, since the court which had awarded K damages and the Court of Protection ought to have been aware that K’s care and treatment gave rise to the first two components of a deprivation of liberty, the positive obligations of article 5 were imposed on the state. Since the deprivation of liberty safeguards in Schedule A1 to the 2005 Act, as inserted, did not apply because the incapacitated person was not in a hospital or care home, responsibility was attributed to the state and, accordingly, a welfare order was necessary to provide a procedure which complied with article 5.

On the Secretary of State’s appeal—

Held, appeal dismissed. The state had a positive obligation under article 5(1) of the Convention to take reasonable steps to prevent arbitrary deprivation of liberty. The current regime of law, supervision and regulations was not sufficient to discharge the state’s article 5 obligation because those bodies and individuals with responsibilities for the quality of care and protection of vulnerable persons in K’s position would only act if someone had drawn concerns as to that particular person’s care and/or support to their attention. The current domestic regime depended on people reporting something wrong at a specific time, which could be particularly problematic in cases where no family members were involved in their care and treatment. It did not meet the state’s obligation under article 5(1) to take reasonable steps to prevent arbitrary deprivation of liberty. Similarly criminal and civil law sanctions which operated retrospectively after arbitrary deprivation of liberty had taken place were insufficient to discharge that positive article 5(1) obligation. There was a need for periodic independent checks on whether the arrangements made for persons in K’s position were in their best interests. Absent the making of a welfare order under section 16(2)(a) of the 2005 Act by the Court of Protection there were insufficient safeguards against arbitrary detention of extremely vulnerable people in a purely private care regime to which the deprivation of liberty safeguards did not apply. The focus in relation to the state’s positive article 5 obligation was entirely on the state’s duty to prevent arbitrary deprivation of liberty, not on the quality of care and treatment actually being provided or whether the best and least restrictive treatment would or would not involve deprivation of the liberty of the individuals concerned (post, paras 62, 68–69, 74–75, 78, 81, 83).

HL v United Kingdom (2004) 40 EHRR 32 Storck v Germany (2005) 43 EHRR 6, Stanev v Bulgaria (2012) 55 EHRR 22, GC and Cheshire West and Chester Council v P (Equality and Human Rights Commission intervening) [2014] AC 896B, SC applied.

Decision of Charles J [2016] EWCOP 27M; [2016] Fam 419; [2016] 3 WLR 867 affirmed.

Appearances:

Rachel Kamm (instructed by Treasury Solicitor) for the Secretary of State; Nageena Khalique QC (instructed by Head of Legal Department, Staffordshire County Council, Stafford) for the local authority; Sam Karim (instructed by Stephensons Solicitors LLP) for the incapacitated adult, by his litigation friend SK; Parishil Patel (instructed by Irwin Mitchell, Sheffield) for the deputy.

Reported by: Susan Denny, Barrister

Full judgment: BAILII

Subject(s):

- Deprivation of liberty🔍

Date: 22/12/16🔍

Court: Court of Appeal (Civil Division)🔍

Judicial history:

Judge(s):

Parties:

Citation number(s):

- [2016] EWCA Civ 1317B

- [2017] WLR(D) 12B

- [2017] Fam 278B, [2017] 2 WLR 1131B, [2017] COPLR 120, [2016] MHLO 55

- Staffordshire County Council v SRK [2016] EWCOP 27

- 39 Essex Chambers, 'Mental Capacity Report' (issue 73, February 2017)

Published: 27/12/16 20:47

Cached: 2024-04-19 01:39:09